"Broke Track Record and Car. Love, Pete."

The following is an excerpt from The Last Lap by William Walker. In this excerpt, read about Pete Kreis's record-breaking experience at the 1925 Grand Prix!

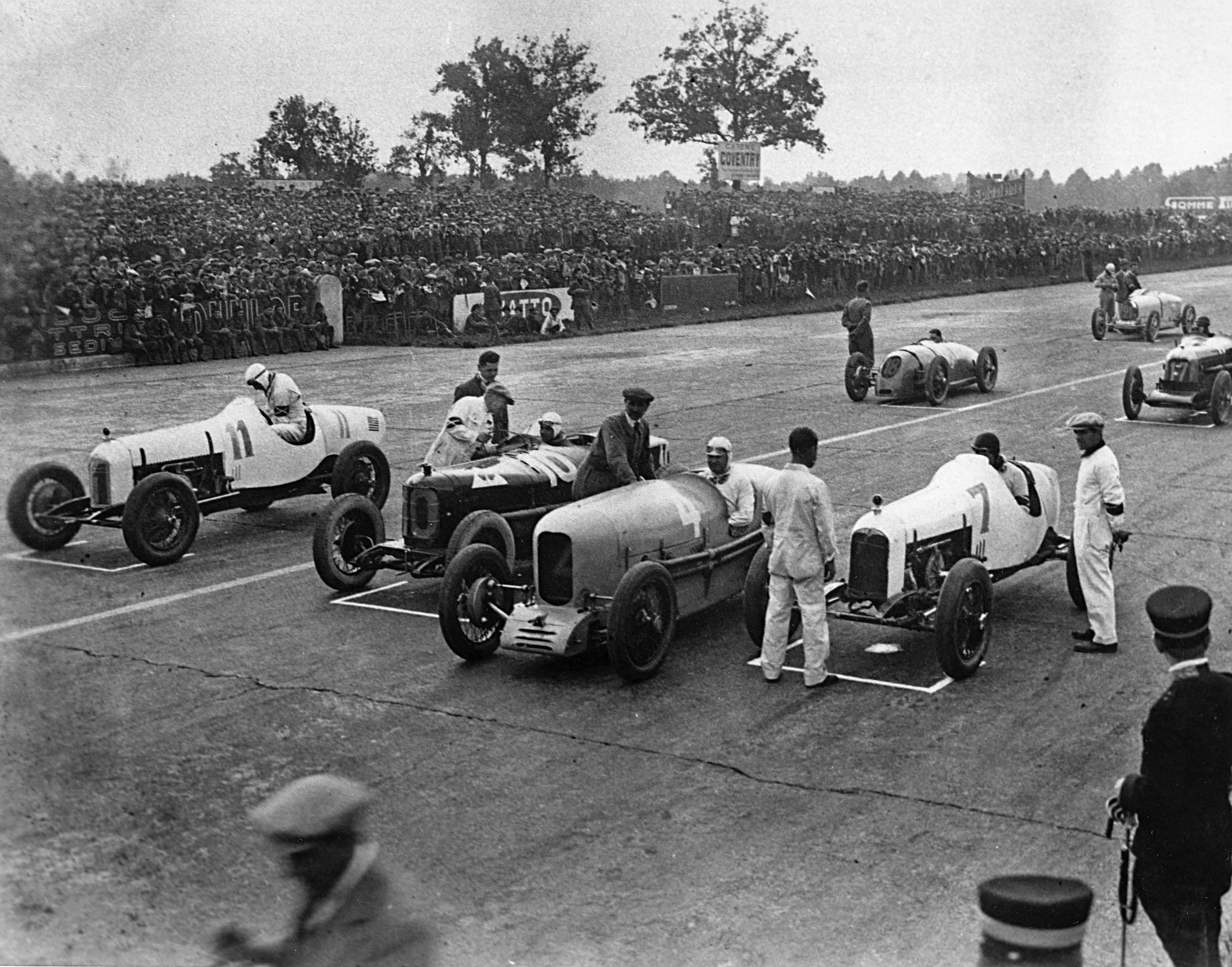

In the 1925 Grand Prix of Europe in Monza, Italy, the American cars arrived at the starting grid sporting new livery: white bodies with blue numbers: veteran Tommy Milton in number 7, novice Pete Kreis in number 11—a not-so-subtle tip of the hat to the Goddess Fortune, who ruled the risky game of auto racing. Small American flags were emblazoned on the rear quarter panels of both machines in a nod to national pride. An estimated 300,000 fans clogged the verge of the track, dwarfing the 180,000 fans who had seen the Indy 500 that year.

The start was from standing positions, and the first to get away was the crowd favorite Giuseppe Campari, followed in order by Albert Guyot, Peter De Paolo, and Kreis. Poor Tommy Milton stalled his engine and got away last, angry steam rising from beneath his cloth helmet.

Campari had the lead when the pack passed the grandstands to finish the first lap, but on the second lap, Pete Kreis had planned a surprise to kick off the anticipated “Italo-American Duel.” When the fans expectantly looked to their right to catch the first glimpse of the cars coming out of the sweeping Parabolica curve at the head of the homestretch, they didn’t see the expected Alfa red, but the American white. Flying around the course, Pete had passed Campari and gone on to establish the fastest lap in the race—three minutes and thirty-five seconds.

This was Kreis at his absolute best, running the race he always envisioned: ahead of the pack, drifting curves with grace, and roaring down the homestretch of his dreams. Drivers often describe this unusual sensation as being “in the zone,” a space magically out of time and place in which racing is easy, effortless, and intuitive. All negative thoughts are vanquished.

“Suddenly I realized that I was no longer driving the car consciously,” Brazilian Formula 1 champion Ayrton Senna said of a similar experience years later. “I was driving it by a kind of instinct, only I was in a different dimension.”

Pete reached that mystical dimension right on time to bring Monza’s crowd to its feet, cheering his achievement. The Americans had likely planned to send Kreis out as a rabbit to tempt the Italians into some hot laps to test their mettle. Then, according to the scheme, Tommy would charge to the front when the forerunners backed off to save their engines. The strategy worked out perfectly, except for Milton’s stalled engine, a disadvantage that Tommy’s skill would soon erase.

As the crowd looked up the homestretch to see who was leading at the end of the third lap, however, they were amazed to see not Kreis in the lead, but Campari. They waited several tense moments, but when Milton’s white roadster appeared before Kreis’s, Italian racing aficionados concluded that Pete had suffered a breakdown or an accident.

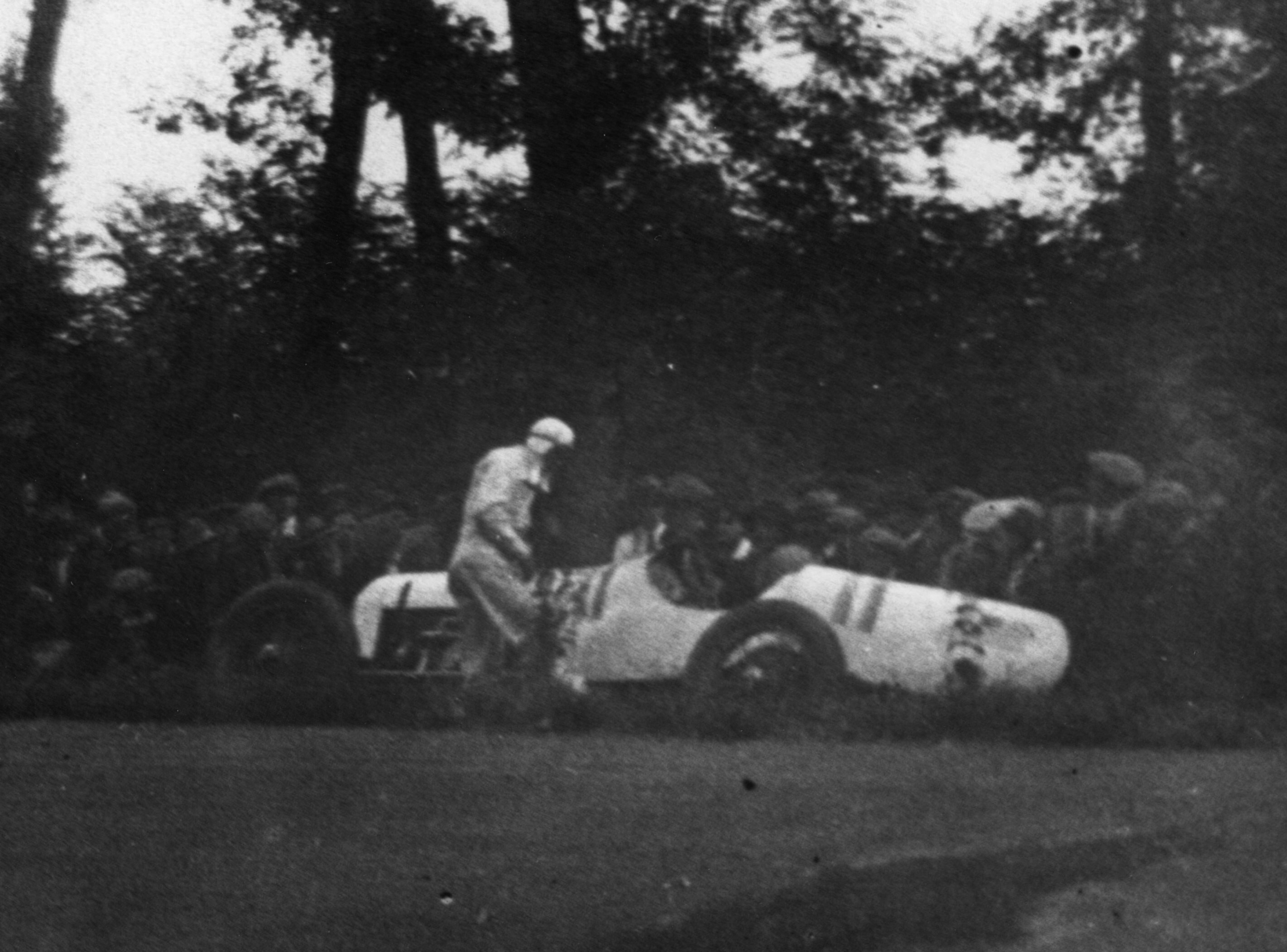

Kreis’s crash happened at Porto Lesmo, a blind, complex curve with dual apexes where he lost control in the first bend. Pete ended up broadside against a tree just off the racing surface; multiple spins had scrubbed off much of his speed so that there was virtually no damage to the Duesenberg. The American driver leapt from the car and put his shoulders to the wheel to push the roadster back on track, but it was wedged too tightly for him to budge it.

Noting his plight, enthusiastic spectators who loved the Americans broke down the restraining barrier and gleefully joined in moving the car back to the track. It was then that Pete envisioned the dreaded black flag in a racing official’s hand: it was forbidden for the drivers to receive assistance from spectators. Kreis would be disqualified. Before that action was taken, however, Pete managed to withdraw from the race, a move that ensured that his new lap record would be preserved for the time being. The crowd gave the American driver a huge ovation for his speed and sportsmanship as he walked back to the pits.

When the flag flashed the finish, Gastone Brilli-Peri, Campari, and De Paolo had claimed podium positions. But given the steep learning curve and the logistical challenges the Americans faced, Milton and Kreis felt that they had represented their nation well, and they looked forward to another opportunity to test themselves against the Europeans—one that would come in 1927.

After a team celebration that extended well into the evening, Pete slipped away to downtown Monza where he located the local telegraph office. On a single white sheet, he scribbled a few words that profoundly confused the Italian telegraph operator but made immediate sense to the US recipient that Pete craved most to please.

“Broke track record and car. Love, Pete,” read the telegram that was delivered to the owner of Riverside Farm, his father, John Kreis.

Check out the related books linked below for more of The Last Lap!