IHC Roots

The International Harvester Company came to exist due in no small part to the business anxiety of Judge Elbert Henry Gary, a lawyer and corporate baron who happens to be the namesake for the town of Gary, Indiana.

In 1901, Judge Gary was chairman of the board of the newly-formed corporate giant, U.S. Steel. He had good reason to be nervous—his company was the largest in the world at the time, and also one of the most highly-leveraged. For him to sleep well, U.S. Steel needed to dominate their industry in unprecedented fashion.

The action he took as a result of his fear would make history.

When Judge Gary stepped into the farm picture in 1901, American harvesting companies were battling over a diminishing slice of business. Demand for reapers, harvesters, and other agricultural equipment was waning, and the next wave of machines powered by gas and steam were not ready for the mass market.

Building ag equipment was a huge American business at that time, as farm technology was transforming the country. The scythe and cradle, the cotton gin, and the cast iron plow allowed fewer people to harvest enough food to feed the rapidly expanding nation.

Farm technology was hot stuff in the 19th century, sort of a rough equivalent of the software revolution today. Check the beard and the button-down shirt and you can see the hipster entrepeneur resemblance . . .

What this meant was the kind of people who today spend their days networking in coffee shops, attending coding meetups, and relentlessly refining their 30-second elevator pitch to mesmerize VC investors and the cast of Shark Tank were focusing their energy into building machines that would more quickly plant and harvest crops.

In America at that time, agricultural technology was roughly equivalent to our present day software revolution: a business that drew geniuses, hucksters, innovators and scam artists to ply their wares with the frantic abandon characteristic of entrepeneurs.

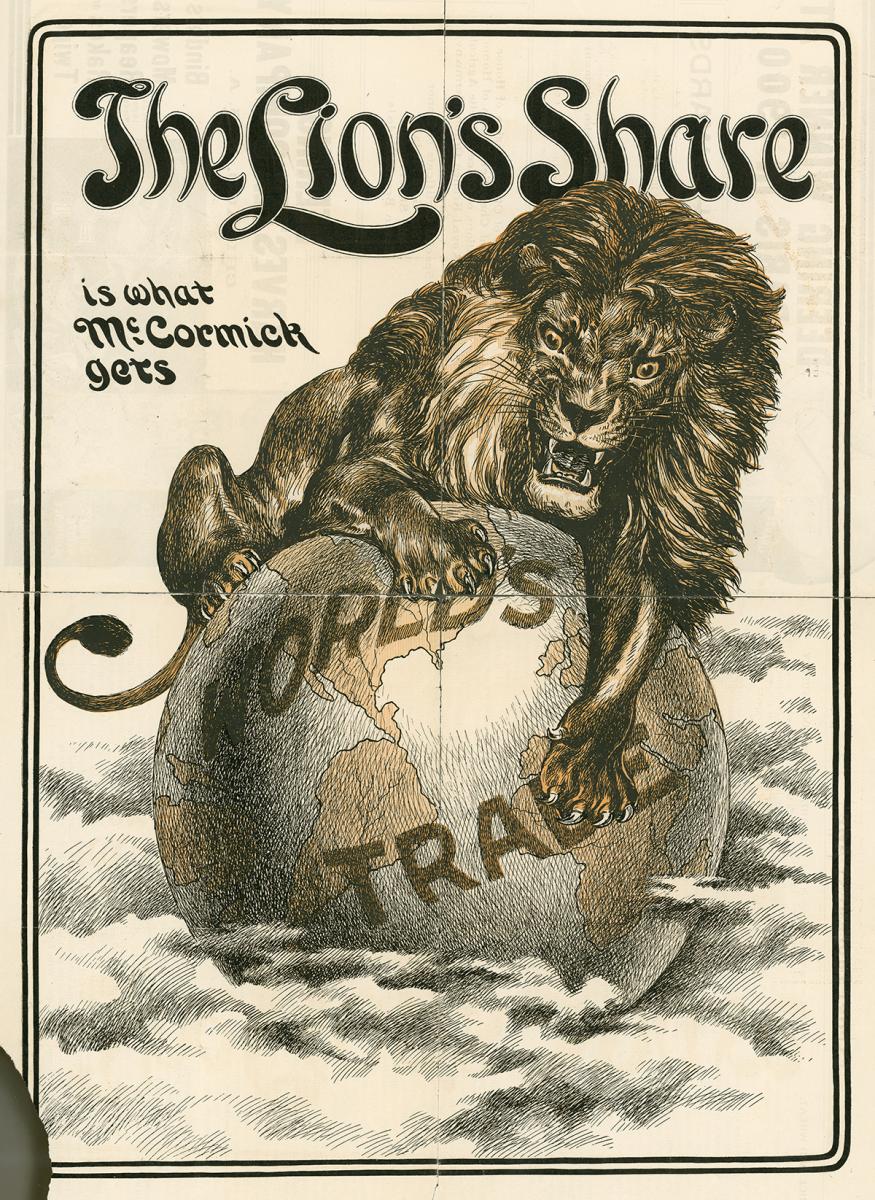

The two largest agricultural equipment manufacturers at the time were McCormick Harvester, founded by Cyrus McCormick, and Deering Harvester, founded by Charles Deering. The two rivals formed their businesses in one of the most hard-fought battlegrounds in the history of American business.

Cyrus founded his company in the 1830s and it grew to become the industry leader. He did so in a bare-knuckled era in which competitors sold equipment with head-to-head demonstrations, dirty tricks, lies, underhanded tactics, and fights in the fields with fists, knives, and sharply-worded posters.

William Deering built a similar agricultural company in the 1870s, and Deering and McCormick duked it out for American farm business for more than three decades.

By 1900, McCormick and Deering each had built massive and powerful American businesses. The company control had passed on to the son of Cyrus McCormick, Cyrus McCormick Junior. William and his son, Charles, controlled Deering.

The two families had all the neighborly tendencies of the Hatfields and the McCoys.

Bear in mind that massive American business mergers were happening at an unprecedented rate between 1899 and 1902. U.S. Steel is the most well-known company founded at the time, a merger that created one of America’s largest companies and made the Rockefeller family one of the richest in the world. Dupont, Eastman Kodak, and General Electric also were formed during this time period. Several of these massive mergers were engineered by legendary banker J.P. Morgan.

J.P. Morgan was an American banker instrumental in creating U.S. Steel and General Electric. He was the inspiration for the banker character in the game Monopoly (left).

From 1899 to 1902, more 132 mergers created massive American companies, with more than half of these consolidations absorbing more than 40 percent of their industry. And nearly a third of these 132 mergers absorbed more than 70 percent of their industry.

Which brings us to our Nervous Nellie Judge Gary. The Judge was the chairman of the board at U.S. Steel, which was formed in 1901. When U.S. Steel was created in 1901, it was valued at $1.4 billion—the world’s first billion-dollar corporation.

U.S. Steel controlled 67 percent of the steel market, but was saddled with a mountain of debt. Investor Andrew Carnegie was so concerned about the company’s precarious cash position that he wouldn’t take a check and his dividend payments were made with gold bullion.

In order to make this big gamble pay off, U.S. Steel needed to dominate their industry. What kept Judge Gary up at night was a concern that the harvesting companies just might purchase their own steel plants and cut U.S. Steel out of the deal.

So in February 1902, Judge Gary suggested to Cyrus McCormick Jr. that there were advantages to be gained from merging the major harvesting manufacturers into one large company.

This wasn’t an entirely new concept to McCormick. In fact, the McCormicks and Deerings had unsuccessfully attempted to merge in 1891, 1897, and 1901. While the arrangement made sense, neither of the leaders was willing to relinquish one ounce of control to their bitter rival.

Judge Gary, however, had an ace in the hole. He brought in George W. Perkins to negotiate the deal. Perkins was a top aide to banker J.P. Morgan, who had engineered the mergers of U.S. Steel and General Electric.

Perkins used a very simple stroke of genius to get the McCormicks and the Deerings to the table; he simply ducked the issue of control entirely by creating a voting trust that would control the company for ten years.

Somehow, he neglected to define how the trust would work, exactly, and the McCormicks and the Deerings each believed they would run the new company. He also brought in three more harvesting companies to be part of the deal.

So in August 1902, five companies with $53 million in annual sales between them were merged to create the International Harvester Company. When it was formed, much of the agricultural equipment manufacturing industry—some estimates say in excess of 80 percent—joined to form a new manufacturer of agricultural machinery. The stated purpose of the merger was to dominate international markets. The truth of the matter is the company would dominate the existing market. It's like Ford, Toyota, Chevy, and Nissan all hopped happily in bed, and grabbed Daimler-Chrysler while they were at it.

The company formed in New Jersey, as the state had enacted lax rules that allowed large corporate mergers to be done with minimal paperwork and taxation. On August 14, 1902, the New York Times reported IHC paid $24,000 to the city of New Jersey for the right to incorporate (one would assume the payment was made in an alley to a guy named Guido, although the Times was not specific about this point).

In the Times piece, an unnamed IHC company spokesman was quoted, offering a large helping of pleasantly-flavored horse excrement stating that the merger was mainly for the farmer’s benefit.

Historians continue to debate the merit of the mergers that took place in this time period, but the fact is that many of these mergers allowed big companies to leverage market dominance to create (and pollute) Gary, Indiana (which was named after Judge Gary), poison the air in Donora, Pennsylvania, and carefully plot to get rich selling light bulbs designed to burn out in short intervals.

Once the IHC deal was done and New Jersey and the J.P. Morgan firm paid off, the voting trust management structure quickly proved a disaster. The voting trust was a group of executives from the five companies plus George W. Perkins, working together as a board of directors for IHC.

The first problem this new board of directors faced was how to effectively merge five warring companies into one, and consolidate their respective networks of management, dealerships, salespeople, factories, and equipment.

Imagine, if you will, the merger between Case and IH. Except, instead of two companies, there are five. And instead of the polite competitiveness that existed between Case and IH, you had five companies who had literally spent three decades beating the tar out of each other in hay fields across America.

Not surprisingly, the board of directors decided to let the five companies continue to operate separately.

This was an understandable if unwise choice for each company owner personally, and a horrid choice for IHC as a whole.

This poor decision was also perhaps the only time the early IHC board of directors were in agreement. The Deerings and McCormicks fought bitterly over every single decision, which often resulted in paralysis. Rather than take advantage of combined distribution, marketing and sales, IHC continued to function as five companies, and net earnings in 1903 dropped 90 percent.

In 1904, the board of directors was dissolved, and Cyrus McCormick Jr was placed in charge. This proved a marginal improvement, as the Deerings continued to fight every move and in fact threatened to take their shares and leave the company. Profits improved only slightly, and company performance continued to lag.

In late 1906, George W. Perkins demanded changes be made. Perkins, incidentally, was part of the problem. Judge Gary came in, and Perkins’ request led to a financial reorganization that gave the Deerings and Perkins no fiscal or managerial control over the company. McCormick Jr. was given complete control of the company.

By 1908, after seven long years of chaos and low profits, IHC’s earnings matched those seen in the founding companies prior to the merger.

The early management structure of IHC was horrid, but the financial structure of the deal that formed the company was solid. In contrast to the U.S. Steel creation, the IHC consolidation created a dominant company that had zero debt load. The company started with a $120 million valuation—pennies compared to Big Daddy Steel at $1.4 billion—but half of the IHC valuation was cold, hard cash. The company had not one nickel of debt.

The first company annual report came out in 1907, and the only mention of the all the management madness and poor performance was a softly-worded apology for “low profits” buried near the back of the report.

Once IHC had their management structure straightened out, they not only were profitable and smart with their cash, they also bought everything under the sun that had to do with their industry. They bought twine manufacturers, lumber mills, forested land, shipping companies, wagon builders, railroads, and more.

And, yes, one of the things they bought was a steel mill, Wisconsin Steel.

Which meant they didn’t have to buy much or any steel from Judge Gary’s company, U.S. Steel.

So Judge Gary’s worries came true, even after the merger he suggested took place. Wisconsin Steel, incidentally, would be a good property for IHC in the first half of the 20th century, and a rolling quagmire of problems in the latter half.

IHC also continued to innovate. The farm equipment business was a prosperous market ripe with new machines. Nearly every time the farm economy boomed, a new technology was brought to market. And the company broadened its reach across the globe, allowing them to push their technology into developing markets in Russia, Europe, India, and more.

All this began first with a rough-hewn young Cyrus McCormick brawling his way from nothing to a massive company, and then a deal engineered by one of America’s most powerful bankers to consolidate the largest agricultural equipment companies under one banner.

That formation would not be legal today—and in fact IHC was sued by the government in 1917 and lost—but the results of the 1902 IHC merger was a company that brought to life new innovations that played key roles in transforming American agriculture and society in the 20th century.

Post by Lee Klancher, author of Red Tractors 1958-2013 and Red Combines 1915-2015, and the photographer who creates the annual Farmall Calendar.