Shooting History: Curveballs and Time Travel

Are you curious to go back in time and explore some International Harvester history with author Lee Klancher? Keep reading to learn about his shoot trip at the prototype International Harvester dealership in Millville, Pennsylvania. This blog was originally published as a feature in the Ageless Iron section of Successful Farming magazine, where Lee Klancher is a regular contributor.

I’m writing from a picnic table at Junction Creek Campground near Durango, Colorado. The air is a sun-soaked but crisp 64 degrees scented with pine, coffee, woodsmoke, and blueberry pancakes. Birds are singing, and the sun is baking the last of the dew off the grass.

Getting here was a bit of an adventure; my wife and I left slightly later than planned, as always seems to happen when we go camping.

We drove all day through rain and threatening skies, and arrived about 7 pm, with the sun low on the horizon and dark clouds rumbling overhead. I had forgotten to sanitize our holding tank, meaning I had to fill it with water and a tiny bit of bleach, let is sit for four hours, flush, and refill.

I had managed to do some of this on the road, but the flush and fill needed doing when we rolled in. Of course, our campground had no water spigot—so the filling was done one six-gallon plastic can at a time.

I frantically filled and poured as the sun faded and the sky darkened. By the time I had our tank safely flushed and partially filled, the light was gone and raindrops were spattering on my hat. As we set up our popup camper, the rain let go with earnest fury and the wind whipped away the warmth of the day.

The minor calamity of unloading in the rain was over and, by 9 pm, we were dry and snug inside, with the end result of cold fingers, a bit of wet gear, and a nice little story to tell.

This started me thinking about life’s propensity to throw curve balls, most often when you are looking for a fastball down the middle.

One of the most remarkable photo shoots I’ve ever done came in Pennsylvania last fall, and as I think about it, I believe the place is an artifact of one of the nastiest curve balls life has ever thrown.

The shoot trip to Pennsylvania is something that has been on my mind for a while. The countryside is beautiful, the farms have distinctive architecture with lots of the age and character I love, and the collector’s organizations are active and have interesting machinery.

Central Pennsylvania was a new frontier as far as I was concerned.

The crowning jewel of the shoot trip was the prototype International Harvester dealership in Millville, Pennsylvania. The dealership is an intact and complete, if a bit frayed around the edges, relic of the glory days of International Harvester agricultural equipment.

I stepped back in time to photograph the vintage IH dealership in Millville, Pennsylvania. Ben Trapani and Marvin Walter of IHCC Chapter 17 seen here at work at the parts.

I stepped back in time to photograph the vintage IH dealership in Millville, Pennsylvania. Ben Trapani and Marvin Walter of IHCC Chapter 17 seen here at work at the parts.

The magic of the dealership is its level of authenticity. When it was closed down in the 1980s, the owners largely left it as it was, with parts stashed in the bins and office and shop equipment laying out after the last job, mostly untouched for roughly two decades.

Thankfully for those of us who love history, the dealership was purchased by the Central Pennsylvania chapter of the International Harvester Collector’s Club. Led by President Ben Trapani, the group raised enough money to purchase the dealership and turn it into a museum.

They use it as their clubhouse and have done a superb job of adding items appropriate to the time period. Tractors now cover the dealership floor and can be seen through the front window. The distinctive Loewy-designed vertical wall above the dealership bears a vintage IH logo, an unmistakable art deco architectural clue that represented a dynasty.

The building is not entirely Loewy’s design, as the owner, Frank Bartlow, was a fiercely independent local entrepreneur who took the early plans for IH dealerships and provided his own additions. That story is chronicled in good detail at www.ihcc17.com, and worth a read. My favorite bit? Bartlow started the project on the opening of deer hunting season in 1946. Having grown up in central Wisconsin, a place where schools close for deer season, I intimately understand the amount of passion and dedication required to miss opening day. I also like that Bartlow started the project in late fall, with winter weather just around the corner. I read him as an optimist, and like the man I see in these actions.

The amount of detail from the past in this dealership—the art deco lettering and vintage clock on the wall above the parts counter, the IH ash trays and letterhead in the office, and the parts still in the bins—collectively create an impression of traveling in time.

Details like the old typewriter on the desk, the classic leather briefcase, and the vintage wood paneling truly make you feel like you are stepping into a different era.

Details like the old typewriter on the desk, the classic leather briefcase, and the vintage wood paneling truly make you feel like you are stepping into a different era.

As I set up an interior photograph with a Farmall M in the foreground and Ben Trapani and Marvin Walter at the parts counter, peering through the lens gave me this sense that four decades had melted away and I was in a dealership living the last days of International Harvester.

I could imagine it was 1979, a pivotal time when a roaring farm economy had farmers ordering new equipment with abandon, goaded on by bankers eager to offer large lines of credit. I have been studying this time for decades, and standing inside it for that shoot, I felt like a time traveler.

IH knew all about debt, and by 1979 the company was saddled with a debt load that started with Fowler McCormick’s egotistical overreach into construction equipment and appliances in the 1950s, coupled with the arrogant oversight of letting their key market—farm tractors—languish with tepid updates and new but hardly revolutionary additions.

IH management in the 1960s wasn’t all that much better and spent most of their energy developing their sales group—which was already the best in the industry—and recovering from Fowler’s missteps. The recovery did not include, unfortunately, significantly paying down their debt. In fact, it grew.

By the early 1970s, the debt load was one of the highest in the equipment industry, and the company’s profit margins one of the lowest. The management team by this time, however, was quite good. Brooks McCormick stepped in, and he was as thoughtful and dedicated as Fowler was unfocused and egotistical.

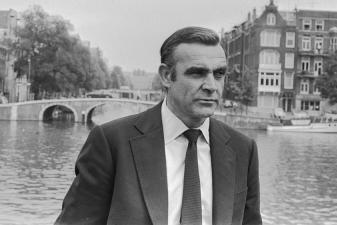

Brooks McCormick was a dapper, respectful man who worked his way up the ranks at IH despite being a direct descendant of the founder. He became a member of IHC senior leadership in 1958 and rose to CEO on November 1, 1971. Photo courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society.

Brooks McCormick was a dapper, respectful man who worked his way up the ranks at IH despite being a direct descendant of the founder. He became a member of IHC senior leadership in 1958 and rose to CEO on November 1, 1971. Photo courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society.

As 1979 faded into 1980, the International Harvester Company—and for that matter the farm—was hit with a plethora of nasty curveballs, knuckleballs, and perhaps the metaphorical equivalent of a bean ball to the head.

Harvester would dig in and take a few deep cuts. The story of triumph and tragedy that took place during that hard-fought time will have to wait until next issue, as I’m out of words and the trail is calling.

If you’d like to read more about the last days of International Harvester, check out Red Tractors by Lee Klancher in the "related books" linked below.

I’m writing from a picnic table at Junction Creek Campground near Durango, Colorado. The air is a sun-soaked but crisp 64 degrees scented with pine, coffee, woodsmoke, and blueberry pancakes. Birds are singing, and the sun is baking the last of the dew off the grass.

Getting here was a bit of an adventure; my wife and I left slightly later than planned, as always seems to happen when we go camping.

We drove all day through rain and threatening skies, and arrived about 7 pm, with the sun low on the horizon and dark clouds rumbling overhead. I had forgotten to sanitize our holding tank, meaning I had to fill it with water and a tiny bit of bleach, let is sit for four hours, flush, and refill.

I had managed to do some of this on the road, but the flush and fill needed doing when we rolled in. Of course, our campground had no water spigot—so the filling was done one six-gallon plastic can at a time.

I frantically filled and poured as the sun faded and the sky darkened. By the time I had our tank safely flushed and partially filled, the light was gone and raindrops were spattering on my hat. As we set up our popup camper, the rain let go with earnest fury and the wind whipped away the warmth of the day.

The minor calamity of unloading in the rain was over and, by 9 pm, we were dry and snug inside, with the end result of cold fingers, a bit of wet gear, and a nice little story to tell.

This started me thinking about life’s propensity to throw curve balls, most often when you are looking for a fastball down the middle.

One of the most remarkable photo shoots I’ve ever done came in Pennsylvania last fall, and as I think about it, I believe the place is an artifact of one of the nastiest curve balls life has ever thrown.

The shoot trip to Pennsylvania is something that has been on my mind for a while. The countryside is beautiful, the farms have distinctive architecture with lots of the age and character I love, and the collector’s organizations are active and have interesting machinery.

Central Pennsylvania was a new frontier as far as I was concerned.

The crowning jewel of the shoot trip was the prototype International Harvester dealership in Millville, Pennsylvania. The dealership is an intact and complete, if a bit frayed around the edges, relic of the glory days of International Harvester agricultural equipment.

I stepped back in time to photograph the vintage IH dealership in Millville, Pennsylvania. Ben Trapani and Marvin Walter of IHCC Chapter 17 seen here at work at the parts.

I stepped back in time to photograph the vintage IH dealership in Millville, Pennsylvania. Ben Trapani and Marvin Walter of IHCC Chapter 17 seen here at work at the parts.The magic of the dealership is its level of authenticity. When it was closed down in the 1980s, the owners largely left it as it was, with parts stashed in the bins and office and shop equipment laying out after the last job, mostly untouched for roughly two decades.

Thankfully for those of us who love history, the dealership was purchased by the Central Pennsylvania chapter of the International Harvester Collector’s Club. Led by President Ben Trapani, the group raised enough money to purchase the dealership and turn it into a museum.

They use it as their clubhouse and have done a superb job of adding items appropriate to the time period. Tractors now cover the dealership floor and can be seen through the front window. The distinctive Loewy-designed vertical wall above the dealership bears a vintage IH logo, an unmistakable art deco architectural clue that represented a dynasty.

The building is not entirely Loewy’s design, as the owner, Frank Bartlow, was a fiercely independent local entrepreneur who took the early plans for IH dealerships and provided his own additions. That story is chronicled in good detail at www.ihcc17.com, and worth a read. My favorite bit? Bartlow started the project on the opening of deer hunting season in 1946. Having grown up in central Wisconsin, a place where schools close for deer season, I intimately understand the amount of passion and dedication required to miss opening day. I also like that Bartlow started the project in late fall, with winter weather just around the corner. I read him as an optimist, and like the man I see in these actions.

The amount of detail from the past in this dealership—the art deco lettering and vintage clock on the wall above the parts counter, the IH ash trays and letterhead in the office, and the parts still in the bins—collectively create an impression of traveling in time.

Details like the old typewriter on the desk, the classic leather briefcase, and the vintage wood paneling truly make you feel like you are stepping into a different era.

Details like the old typewriter on the desk, the classic leather briefcase, and the vintage wood paneling truly make you feel like you are stepping into a different era.As I set up an interior photograph with a Farmall M in the foreground and Ben Trapani and Marvin Walter at the parts counter, peering through the lens gave me this sense that four decades had melted away and I was in a dealership living the last days of International Harvester.

I could imagine it was 1979, a pivotal time when a roaring farm economy had farmers ordering new equipment with abandon, goaded on by bankers eager to offer large lines of credit. I have been studying this time for decades, and standing inside it for that shoot, I felt like a time traveler.

IH knew all about debt, and by 1979 the company was saddled with a debt load that started with Fowler McCormick’s egotistical overreach into construction equipment and appliances in the 1950s, coupled with the arrogant oversight of letting their key market—farm tractors—languish with tepid updates and new but hardly revolutionary additions.

IH management in the 1960s wasn’t all that much better and spent most of their energy developing their sales group—which was already the best in the industry—and recovering from Fowler’s missteps. The recovery did not include, unfortunately, significantly paying down their debt. In fact, it grew.

By the early 1970s, the debt load was one of the highest in the equipment industry, and the company’s profit margins one of the lowest. The management team by this time, however, was quite good. Brooks McCormick stepped in, and he was as thoughtful and dedicated as Fowler was unfocused and egotistical.

Brooks McCormick was a dapper, respectful man who worked his way up the ranks at IH despite being a direct descendant of the founder. He became a member of IHC senior leadership in 1958 and rose to CEO on November 1, 1971. Photo courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society.

Brooks McCormick was a dapper, respectful man who worked his way up the ranks at IH despite being a direct descendant of the founder. He became a member of IHC senior leadership in 1958 and rose to CEO on November 1, 1971. Photo courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society.As 1979 faded into 1980, the International Harvester Company—and for that matter the farm—was hit with a plethora of nasty curveballs, knuckleballs, and perhaps the metaphorical equivalent of a bean ball to the head.

Harvester would dig in and take a few deep cuts. The story of triumph and tragedy that took place during that hard-fought time will have to wait until next issue, as I’m out of words and the trail is calling.

If you’d like to read more about the last days of International Harvester, check out Red Tractors by Lee Klancher in the "related books" linked below.